The Artist, Manu3l Beauty, Drawing Lo, as Drawn by Manu3l Beauty

In the first volume of Parerga und Paralipomena I read again that everything which can happen to a man, from the instant of his birth until his death, has been preordained by him. Thus, every negligence is deliberate, every chance encounter an appointment, every humiliation a penitence, every failure a mysterious victory, every death a suicide.

Jorge Luis Borges

Labyrinths, from the story, “Deutsches Requiem” p. 143

Ever since I first read Henry James’ The Portrait of a Lady, I knew what I wanted to write: the antithetical portrait. I wanted to write a response to the ever upright, ever virtuous, ever socially acceptable Isabel Archer. I was young when I read Portrait, still, it had a profound effect on me. I found it a struggle to read each and every painstaking page. The rectitude of the protagonist grated on me. Her compliance to social norms caused the hairs on the back of my neck to stand on end. Her pathetic powerlessness at the hands of the pervasive patriarchy outraged me.

By the time I had read Portrait, I had already loved and left my lusty slut to whom I had lost my virginity. Her nymphomaniacal ways were beyond my limited abilities to assimilate into my concept of the world at that tender age. But, as I read Portrait, I knew, with every fiber of my being, that I wanted to strip Isabel of her honor and her clothes.

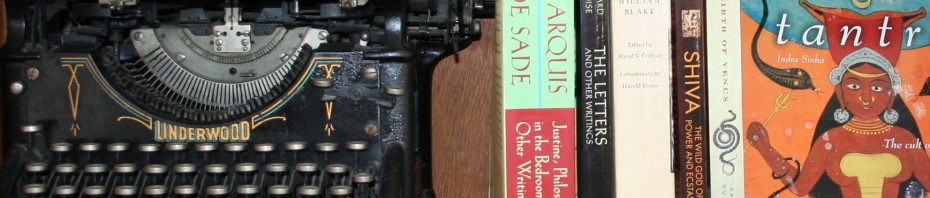

The idea remained and germinated in my mind over many years. When, at a more advanced age, I had read the collected works of the Marquis de Sade, I thought at first that I was too late. Someone had written the great work I envisioned since reading Henry James. However, the more I read of Sade, the more I realized that no, this is not the work I envisioned. Sade is brilliant, imaginative, subversive, and powerful. He was an important voice for his time and, despite many detractors, he actually offers a harsh critique of religious institutions, monarchy, marriage, and all the other permutations of patriarchy. He spares none in his scathing evaluation of oppression in all its forms. But his protest is essentially a resounding No! That was important for his era, but what he lacks, probably because it was unimaginable at the time, was a heroine who could proclaim a resounding Yes!

All of Sade’s fictional female figures are victims. They may also be villains, but they are so only because they were first victims. Hurt people hurt people, as the saying goes. They were formed by the social, political, religious, judicial, and educational systems, hierarchies, and prejudices of their culture. What Sade was really up to is open to debate, but a charitable reading could be that he was shining a light on the gender injustices of his day and, even if his medium of doing so was “sadistic” (a term that was invented because of him), it also was sympathetic to the plight of women.

But I longed to write The Great American Novel that told a different story. Not the story of Justine, not the story of Juliette, and certainly not the story of Isabel Archer! I wanted to write the story of a sex-positive woman who claimed her own sexuality, her female form, her feminine facticity, her healthy desires, her sexual conquests, her orgasms, her self-pleasure, and her liberal lending of her labia as her own in a way that was not the result of victimhood and was not wielded as vindictiveness. In other words, I wanted a sexual heroine, not an anti-heroine, despite how some retrograde segments of our modern society might still view such a character.

Perhaps that deep-seated vision of a new dawn was responsible for drawing me into Lo’s orbit and then, ultimately, for my “drawing” her in my writings as the woman of my dreams. I cannot deny that Lo, when I met her, was not already without scars from the injustices of society, family, and past sexual partners. But she was not a victim. She was, even then, well on her way to inhabiting her own power. She was healing. Through obstacles, with love and support, encouragement and empathy, she (re)claimed her puss and her prowess.

Lo might not have escaped the perils of being born a woman, but she has transformed her trauma into a personal triumph. I endeavor to portray Lo not as a perfect portrait of feminine form, but as a realistic rendition of a flawed, fallible figure; made all the more beautiful by her unique imperfections.

I love Lola not because she is flawless, but because of her wabi-sabi character. I love her the way Woody Allen loved New York City of the ’70’s. Back then, the city was far from perfect. She had her many ugly sides. But he was in love with her and wanted to tell her stories to the world, to get the world to see her the way he saw her. To get the world to fall in love with her just as he had.

Writing about Lo is not only my love letter to her, but, as so many who have read about her have told us, her story is also a vehicle to help others become as daring, confident, and self-actualizing as Lo, because perfect people don’t perfect people, but healed people can heal people.

Exactly so spotless

Beautifully put

You inspire me H.H., I am fortunate t be living and loving a woman who is challenging the norms. Who explores her appetites and in the process has helped me grow. Your stories have helped me understand and overcome my jealousy. To think less like my patriarchal upbringing and with more of an open mind. To recognize it is about her exploring her pleasure and not all about me. Thank you

So glad to hear it!